U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Materials for Electronic Access: Creation of Production Master Files -- Raster Images For the Following Record Types -- Textual, Graphic Illustrations/Artwork/Originals, Maps, Plans, Oversized, Photographs, Aerial Photographs, and Objects/Artifacts June 2004Written by Steven Puglia, Jeffrey Reed, and Erin RhodesDigital Imaging Lab, Special Media Preservation Laboratory, Preservation Programs Acknowledgements: Thank you to Dr. Don Williams for target analyses, technical guidance based on his extensive experience, and assistance on the assessment of digital capture devices. Thank you to the following for reading drafts of these guidelines and providing comments: Stephen Chapman, Bill Comstock, Maggie Hale, and David Remington of Harvard University; Phil Michel and Kit Peterson of the Library of Congress; and Doris Hamburg, Kitty Nicholson, and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. The NARA Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Materials for Electronic Access define approaches for creating digital surrogates for facilitating access and reproduction; they are not considered appropriate for preservation reformatting to create surrogates that will replace original records. The Technical Guidelines presented here are based on the procedures used by the Digital Imaging Lab of NARA's Special Media Preservation Laboratory for digitizing archival records and the creation of production master image files, and are a revision of the 1998 "NARA Guidelines for Digitizing Archival Materials for Electronic Access", which describes the imaging approach used for NARA's pilot Electronic Access Project. The Technical Guidelines are intended to be informative, and not intended to be prescriptive. We hope to provide a technical foundation for digitization activities, but further research will be necessary to make informed decisions regarding all aspects of digitizing projects. These guidelines provide a range of options for various technical aspects of digitization, primarily relating to image capture, but do not recommend a single approach. The intended audience for these guidelines includes those who will be planning, managing, and approving digitization projects, such as archivists, librarians, curators, managers, and others. Another primary audience includes those actually doing scanning and digital capture, such as technicians and photographers.

-2-

-3-

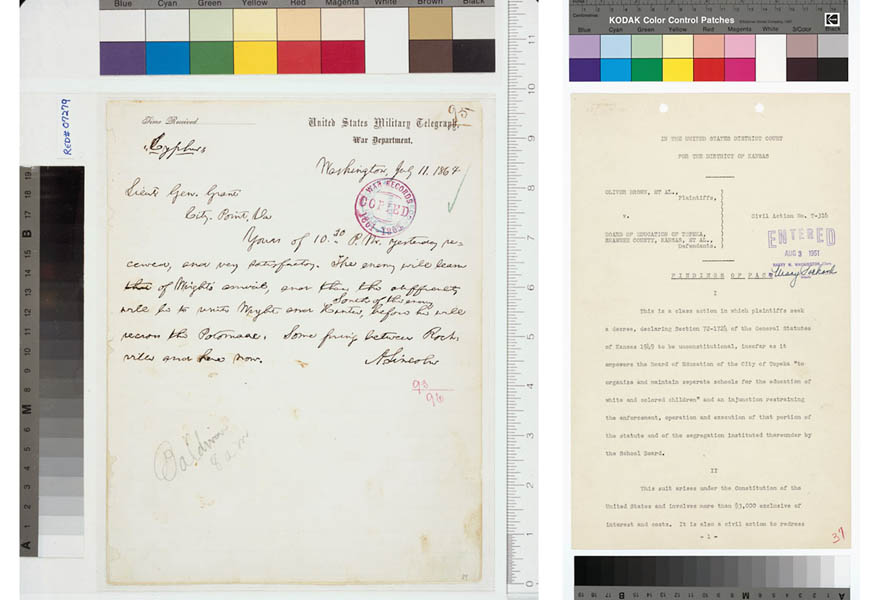

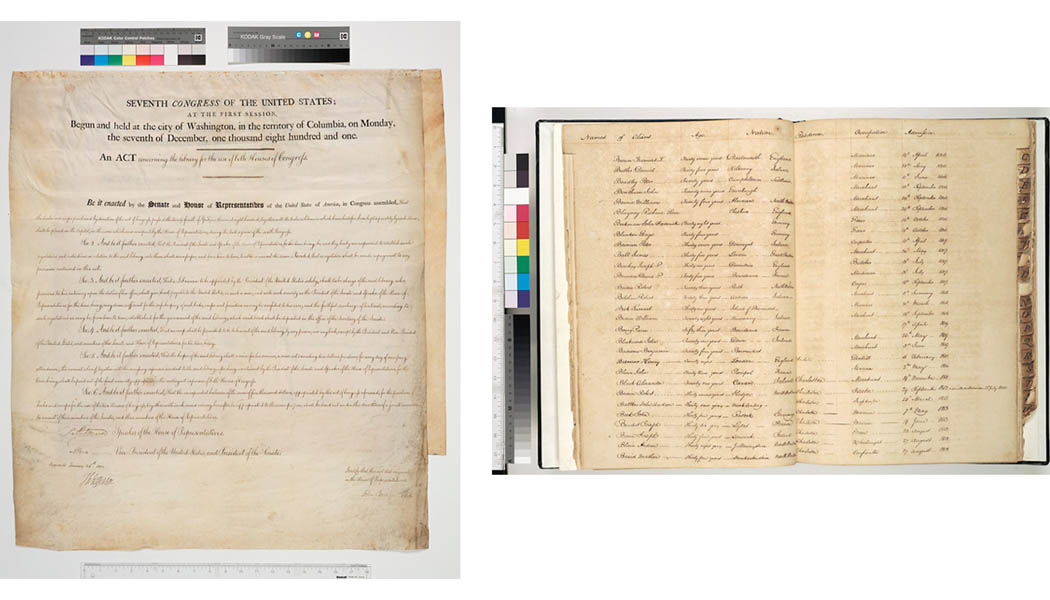

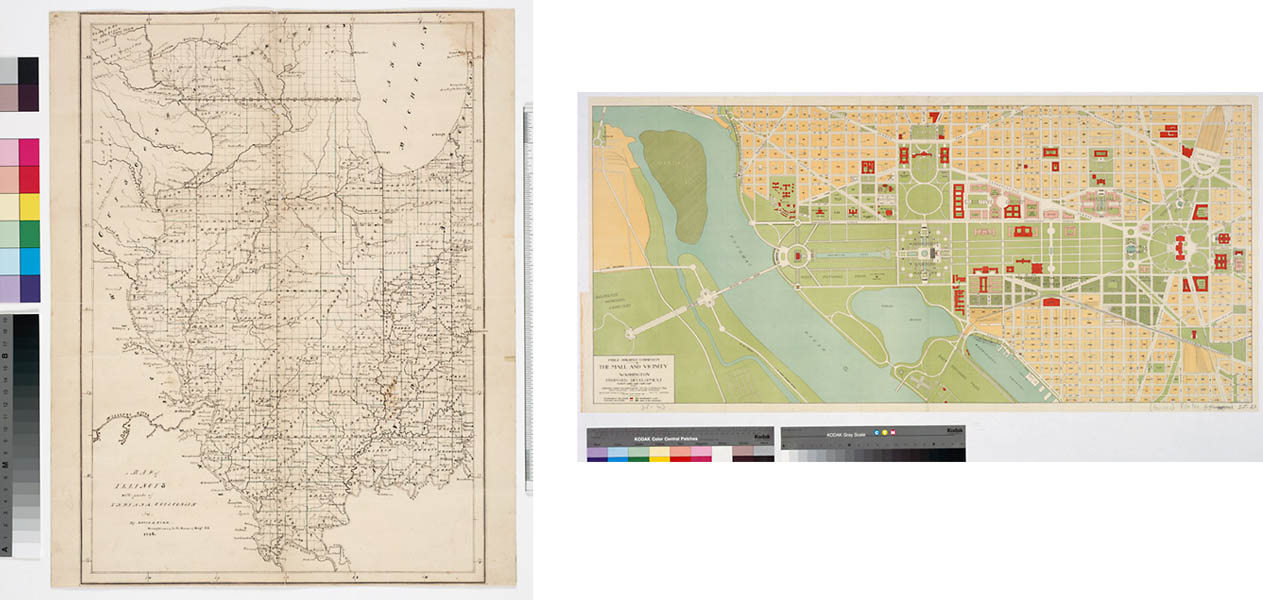

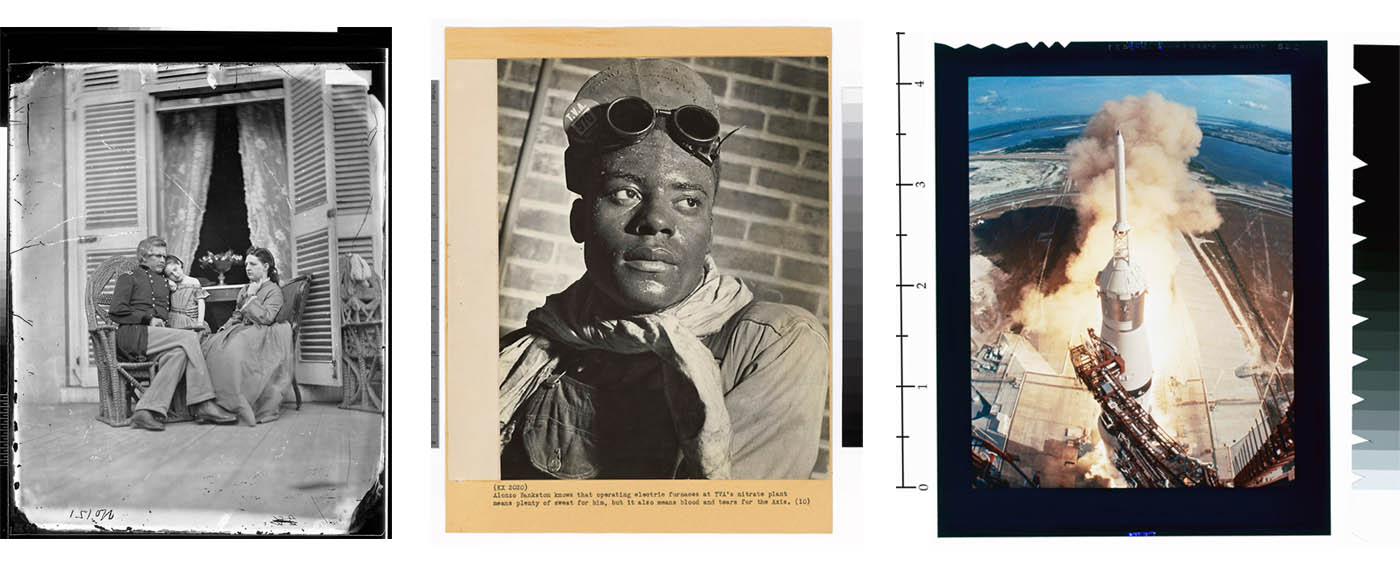

-5- I. INTRODUCTIONThese Guidelines define approaches for creating digital surrogates for facilitating access and reproduction. They are not considered appropriate for preservation reformatting to create surrogates that will replace original records. For further discussion of the differences between these two approaches, see Appendix A, Digitization for Preservation vs. Production Masters. These guidelines provide technical benchmarks for the creation of "production master" raster image (pixel-based) files. Production masters are files used for the creation of additional derivative files for distribution and/or display via a monitor and for reproduction purposes via hardcopy output at a range of sizes using a variety of printing devices (see Appendix B, Derivative Files, for more information). Our aim is to use the production master files in an automated fashion to facilitate affordable reprocessing. Many of the technical approaches discussed in these guidelines are intended for this purpose. Production master image files have the following attributes --

If your intended usage for production master image files is different and you do not need all the potential capabilities of images produced to meet the recommended image parameters, then you should select appropriate image parameters for your project. In other words, your approach to digitization may differ and should be tailored to the specific requirements of the project. Generally, given the high costs and effort for digitization projects, we do not recommend digitizing to anything less than our alternative minimum image parameters. This assumes availability of suitable high-quality digitization equipment that meets the assessment criteria described below (see Quantifying Scanner/Digital Camera Performance) and produces image files that meet the minimum quality described in the Technical Guidelines. If digitization equipment fails any of the assessment criteria or is unable to produce image files of minimum quality, then it may be desirable to invest in better equipment or to contract with a vendor for digitization services. II. METADATANOTE: All digitization projects undertaken at NARA and covered by NARA 816 Digitizing Activities for Enhanced Access, including those involving partnerships with outside organizations, must ensure that descriptive information is prepared in accordance with NARA 1301 Life Cycle Data Standards and Lifecycle Authority Control, at http://www.nara-at-work.gov/nara_policies_and_guidance/directives/1300_series/nara1301.html (NARA internal link only), and its associated Lifecycle Data Requirements Guide, and added to NARA's Archival Research Catalog (ARC) at a time mutually agreed-upon with NARA. -6- Although there are many technical parameters discussed in these Guidelines that define a high-quality production master image file, we do not consider an image to be of high quality unless metadata is associated with the file. Metadata makes possible several key functions -- the identification, management, access, use, and preservation of a digital resource -- and is therefore directly associated with most of the steps in a digital imaging project workflow: file naming, capture, processing, quality control, production tracking, search and retrieval design, storage, and long-term management. Although it can be costly and time-consuming to produce, metadata adds value to production master image files: images without sufficient metadata are at greater risk of being lost. No single metadata element set or standard will be suitable for all projects or all collections. Likewise, different original source formats (text, image, audio, video, etc.) and different digital file formats may require varying metadata sets and depths of description. Element sets should be adapted to fit requirements for particular materials, business processes and system capabilities. Because no single element set will be optimal for all projects, implementations of metadata in digital projects are beginning to reflect the use of "application profiles," defined as metadata sets that consist of data elements drawn from different metadata schemes, which are combined, customized and optimized for a particular local application or project. This "mixing and matching" of elements from different schemas allows for more useful metadata to be implemented at the local level while adherence to standard data values and structures is still maintained. Locally-created elements may be added as extensions to the profile, data elements from existing schemas might be modified for specific interpretations or purposes, or existing elements may be mapped to terminology used locally. Because of the likelihood that heterogeneous metadata element sets, data values, encoding schemes, and content information (different source and file formats) will need to be managed within a digital project, it is good practice to put all of these pieces into a broader context at the outset of any project in the form of a data or information model. A model can help to define the types of objects involved and how and at what level they will be described (i.e., are descriptions hierarchical in nature, will digital objects be described at the file or item level as well as at a higher aggregate level, how are objects and files related, what kinds of metadata will be needed for the system, for retrieval and use, for management, etc.), as well as document the rationale behind the different types of metadata sets and encodings used. A data model informs the choice of metadata element sets, which determine the content values, which are then encoded in a specific way (in relational database tables or an XML document, for example). Although there is benefit to recording metadata on the item level to facilitate more precise retrieval of images within and across collections, we realize that this level of description is not always practical. Different projects and collections may warrant more in-depth metadata capture than others; a deep level of description at the item level, however, is not usually accommodated by traditional archival descriptive practices. The functional purpose of metadata often determines the amount of metadata that is needed. Identification and retrieval of digital images may be accomplished on a very small amount of metadata; however, management of and preservation services performed on digital images will require more finely detailed metadata -- particularly at the technical level, in order to render the file, and at the structural level, in order to describe the relationships among different files and versions of files. Metadata creation requires careful analysis of the resource at hand. Although there are current initiatives aimed at automatically capturing a given set of values, we believe that metadata input is still largely a manual process and will require human intervention at many points in the object's lifecycle to assess the quality and relevance of metadata associated with it. This section of the Guidelines serves as a general discussion of metadata rather than a recommendation of specific metadata element sets; although several elements for production master image files are suggested as minimum-level information useful for basic file management. We are currently investigating how we will implement and formalize technical and structural metadata schemes into our workflow and anticipate that this section will be updated on a regular basis. Common Metadata Types:Several categories of metadata are associated with the creation and management of production master image files. The following metadata types are the ones most commonly implemented in imaging projects. Although these categories are defined separately below, there is not always an obvious distinction between them, since each type contains elements that are both descriptive and administrative in nature. These types are commonly broken down by what functions the metadata supports. In general, the types of metadata listed below, except for descriptive, are usually found "behind the scenes" in databases rather than in public access systems. As a result, these types of metadata tend to be less standardized and more aligned with local requirements. -7- Descriptive --Descriptive metadata refers to information that supports discovery and identification of a resource (the who, what, when and where of a resource). It describes the content of the resource, associates various access points, and describes how the resource is related to other resources intellectually or within a hierarchy. In addition to bibliographic information, it may also describe physical attributes of the resource such as media type, dimension, and condition. Descriptive metadata is usually highly structured and often conforms to one or more standardized, published schemes, such as Dublin Core or MARC. Controlled vocabularies, thesauri, or authority files are commonly used to maintain consistency across the assignment of access points. Descriptive information is usually stored outside of the image file, often in separate catalogs or databases from technical information about the image file. Although descriptive metadata may be stored elsewhere, it is recommended that some basic descriptive metadata (such as a caption or title) accompany the structural and technical metadata captured during production. The inclusion of this metadata can be useful for identification of files or groups of related files during quality review and other parts of the workflow, or for tracing the image back to the original. Descriptive metadata is not specified in detail in this document; however, we recommend the use of the Dublin Core Metadata

Element [1] set to capture minimal descriptive metadata information where metadata in another formal data standard does not exist. Metadata

should be collected directly in Dublin Core; if it is not used for direct data collection, a mapping to Dublin Core elements

is recommended. A mapping to Dublin Core from a richer, local metadata scheme already in use may also prove helpful for data

exchange across other projects utilizing Dublin Core. Not all Dublin Core elements are required in order to create a valid

Dublin Core record. However, we suggest that production master images be accompanied by the following elements at the very

minimum:

These selected elements serve the purpose of basic identification of a file. Additionally, the Dublin Core elements "Format" (describes data types) and "Type" (describes limited record types) may be useful in certain database applications where sorting or filtering search results across many record genres or data types may be desirable. Any local fields that are important within the context of a particular project should also be captured to supplement Dublin Core fields so that valuable information is not lost. We anticipate that selection of metadata elements will come from more than one preexisting element set -- elements can always be tailored to specific formats or local needs. Projects should support a modular approach to designing metadata to fit the specific requirements of the project. Standardizing on Dublin Core supplies baseline metadata that provides access to files, but this should not exclude richer metadata that extends beyond the Dublin Core set, if available. For large-scale digitization projects, only minimal metadata may be affordable to record during capture, and is likely to consist of linking image identifiers to page numbers and indicating major structural divisions or anomalies of the resource (if applicable) for text documents. For photographs, capturing caption information (and Still Photo identifier) is ideal. For other non-textual materials, such as posters and maps, descriptive information taken directly from the item being scanned as well as a local identifier should be captured. If keying of captions into a database is prohibitive, if possible scan captions as part of the image itself. Although this information will not be searchable, it will serve to provide some basis of identification for the subject matter of the photograph. Recording of identifiers is important for uniquely identifying resources and is necessary for locating and managing them. It is likely that digital images will be associated with more than one identifier -- for the image itself, for metadata or database records that describe the image, and for reference back to the original. Dublin Core Metadata Initiative, (http://dublincore.org/usage/terms/dc/current-elements/). The Dublin Core element set is

characterized by simplicity in creation of records, flexibility, and extensibility. It facilitates description of all types

of resources and is intended to be used in conjunction with other standards that may offer fuller descriptions in their respective

domains. For images to be entered into NARA's Archival Research Catalog (ARC), a more detailed complement of metadata is required. For a more detailed discussion of descriptive metadata requirements for digitization projects at NARA, -8- we refer readers to NARA's Lifecycle Data Requirements Guide (LCDRG), at: http://www.archives.gov/research_room/arc/arc_info/lifecycle_data_requirements.doc (June 2004), and NARA internal link -- http://www.nara-at-work.gov/archives_and_records_mgmt/archives_and_activities/accessioning_processing_description/lifecycle/index.html (January 2002), which contains data elements developed for the archival description portion of the records lifecycle, and associates these elements with many different hierarchical levels of archival materials from record groups to items. The LCDRG also specifies rules for data entry. The LCDRG also requires a minimum set of other metadata to be recorded for raster image files at the file level, including technical metadata that enables images to display properly in the ARC interface.Additionally, enough compatibility exists between Dublin Core and the data requirements that NARA has developed for archival description to provide a useful mapping between data elements, if a digital project requires that metadata also be managed locally (outside of ARC), perhaps in a local database or digital asset management system that supports data in Dublin Core. Please see Appendix C for a listing of mandatory elements identified in the Lifecycle Data Requirements Guide at the record group, series, file unit and item level, with Dublin Core equivalents. Because ARC will be used as the primary source for descriptive information about the holdings of permanent records at NARA, we refer readers to the LCDRG framework rather than discuss Encoded Archival Description (EAD) of finding aids. NARA has developed its own hierarchical descriptive structure that relates to Federal records in particular, and therefore has not implemented EAD locally. However, because of the prevalence of the use of EAD in the wider archival and digitization communities, we have included a reference here. For more information on EAD, see the official EAD site at the Library of Congress at http://lcweb.loc.gov/ead/; as well as the Research Library Group's Best Practices Guidelines for EAD at http://www.rlg.org/rlgead/eadguides.html. Administrative --The Dublin Core set does not provide for administrative, technical, or highly structured metadata about different document types. Administrative metadata comprises both technical and preservation metadata, and is generally used for internal management of digital resources. Administrative metadata may include information about rights and reproduction or other access requirements, selection criteria or archiving policy for digital content, audit trails or logs created by a digital asset management system, persistent identifiers, methodology or documentation of the imaging process, or information about the source materials being scanned. In general, administrative metadata is informed by the local needs of the project or institution and is defined by project-specific workflows. Administrative metadata may also encompass repository-like information, such as billing information or contractual agreements for deposit of digitized resources into a repository. For additional information, see Harvard University Library's Digital Repository Services (DRS) User Manual for Data Loading, Version 2.04 at http://hul.harvard.edu/ois/systems/drs/drs_load_manual.pdf, particularly Section 5.0, "DTD Element Descriptions" for application of administrative metadata in a repository setting; Making of America 2 (MOA2) Digital Object Standard: Metadata, Content, and Encoding at http://www.cdlib.org/about/publications/CDLObjectStd-2001.pdf; the Dublin Core also has an initiative for administrative metadata at http://metadata.net/admin/draft-iannella-admin-01.txt in draft form as it relates to descriptive metadata. The Library of Congress has defined a data dictionary for various formats in the context of METS, Data Dictionary for Administrative Metadata for Audio, Image, Text, and Video Content to Support the Revision of Extension Schemas for METS, available at http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mopic/avprot/extension2.html. Rights --Although metadata regarding rights management information is briefly mentioned above, it encompasses an important piece of administrative metadata that deserves further discussion. Rights information plays a key role in the context of digital imaging projects and will become more and more prominent in the context of preservation repositories, as strategies to act upon digital resources in order to preserve them may involve changing their structure, format, and properties. Rights metadata will be used both by humans to identify rights holders and legal status of a resource, and also by systems that implement rights management functions in terms of access and usage restrictions. Because rights management and copyright are complex legal topics, the General Counsel's office (or a lawyer) should be consulted for specific guidance and assistance. The following discussion is provided for informational purposes only and should not be considered specific legal advice. Generally, records created by employees of the Federal government as part of their routine duties, works for hire created under contract to the Federal government, and publications produced by the Federal government are all in -9- the public domain. However, it is not enough to assume that if NARA has physical custody of a record that it also owns the intellectual property in that record. NARA also has custody of other records, where copyright may not be so straightforward -- such as personal letters written by private individuals, personal papers from private individuals, commercially published materials of all types, etc. -- which are subject to certain intellectual property and privacy rights and may require additional permissions from rights holders. After transfer or donation of records to NARA from other federal agencies or other entities, NARA may either: own both the physical record and the intellectual property in the record; own the physical record but not the intellectual property; or the record is in the public domain. It is important to establish who owns or controls both the physical record and the copyright at the beginning of an imaging project, as this affects reproduction, distribution, and access to digital images created from these records.Metadata element sets for intellectual property and rights information are still in development, but they will be much more detailed than statements that define reproduction and distribution policies. At a minimum, rights-related metadata should include: the legal status of the record; a statement on who owns the physical and intellectual aspects of the record; contact information for these rights holders; as well as any restrictions associated with the copying, use, and distribution of the record. To facilitate bringing digital copies into future repositories, it is desirable to collect appropriate rights management metadata at the time of creation of the digital copies. At the very least, digital versions should be identified with a designation of copyright status, such as: "public domain;" "copyrighted" (and whether clearance/permissions from rights holder has been secured); "unknown;" "donor agreement/contract;" etc. Preservation metadata dealing with rights management in the context of digital repositories will likely include detailed information on the types of actions that can be performed on data objects for preservation purposes and information on the agents or rights holders that authorize such actions or events. For an example of rights metadata in the context of libraries and archives, a rights extension schema has recently been added to the Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS), which documents metadata about the intellectual rights associated with a digital object. This extension schema contains three components: a rights declaration statement; detailed information about rights holders; and context information, which is defined as "who has what permissions and constraints within a specific set of circumstances." The schema is available at: http://www.loc.gov/standards/rights/METSRights.xsd. For additional information on rights management, see: Peter B. Hirtle, "Archives or Assets?" at http://techreports.library.cornell.edu:8081/Dienst/UI/1.0/Display/cul.lib/2003-2; June M. Besek, Copyright Issues Relevant to the Creation of a Digital Archive: A Preliminary Assessment, January 2003 at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub112/contents.html; Adrienne Muir, "Copyright and Licensing for Digital Preservation," at http://www.cilip.org.uk/update/issues/jun03/article2june.html; Karen Coyle, Rights Expression Languages, A Report to the Library of Congress, February 2004, available at http://www.loc.gov/standards/Coylereport_final1single.pdf; MPEG-21 Overview v.5 contains a discussion on intellectual property and rights at http://www.chiariglione.org/mpeg/standards/mpeg-21/mpeg-21.htm; for tables that reference when works pass into the public domain, see Peter Hirtle, "When Works Pass Into the Public Domain in the United States: Copyright Term for Archivists and Librarians," at http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/training/Hirtle_Public_Domain.htm and Mary Minow, "Library Digitization Projects: Copyrighted Works that have Expired into the Public Domain" at http://www.librarylaw.com/DigitizationTable.htm; and for a comprehensive discussion on libraries and copyright, see: Mary Minow, Library Digitization Projects and Copyright at http://www.llrx.com/features/digitization.htm. Technical --Technical metadata refers to information that describes attributes of the digital image (not the analog source of the image) and helps to ensure that images will be rendered accurately. It supports content preservation by providing information needed by applications to use the file and to successfully control the transformation or migration of images across or between file formats. Technical metadata also describes the image capture process and technical environment, such as hardware and software used to scan images, as well as file format-specific information, image quality, and information about the source object being scanned, which may influence scanning decisions. Technical metadata helps to ensure consistency across a large number of files by enforcing standards for their creation. At a minimum, technical metadata should capture the information necessary to render, display, and use the resource. Technical metadata is characterized by information that is both objective and subjective -- attributes of image quality that can be measured using objective tests as well as information that may be used in a subjective assessment of an image's value. Although tools for automatic creation and capture of many objective components -10- are badly needed, it is important to determine what metadata should be highly structured and useful to machines, as opposed to what metadata would be better served in an unstructured, free-text note format. The more subjective data is intended to assist researchers in the analysis of digital resource or imaging specialists and preservation administrators in determining long-term value of a resource.In addition to the digital image, technical metadata will also need to be supplied for the metadata record itself if the metadata is formatted as a text file or XML document or METS document, for example. In this sense, technical metadata is highly recursive, but necessary for keeping both images and metadata understandable over time. Requirements for technical metadata will differ for various media formats. For digital still images, we refer to the NISO Data Dictionary -- Technical Metadata for Digital Still Images at http://www.niso.org/standards/resources/Z39_87_trial_use.pdf. It is a comprehensive technical metadata set based on the Tagged Image File Format specification, and makes use of the data that is already captured in file headers. It also contains metadata elements important to the management of image files that are not present in header information, but that could potentially be automated from scanner/camera software applications. An XML schema for the NISO technical metadata has been developed at the Library of Congress called MIX (Metadata in XML), which is available at http://www.loc.gov/standards/mix/. See also the TIFF 6.0 Specification at http://partners.adobe.com/asn/developer/pdfs/tn/TIFF6.pdf as well as the Digital Imaging Group's DIG 35 metadata element set at http://www.i3a.org/i_dig35.html; and Harvard University Library's Administrative Metadata for Digital Still Images data dictionary at http://hul.harvard.edu/ldi/resources/ImageMetadata_v2.pdf. A new initiative led by the Research Libraries Group called "Automatic Exposure: Capturing Technical Metadata for Digital Still Images" is investigating ways to automate the capture of technical metadata specified in the NISO Z39.87 draft standard. The initiative seeks to build automated capture functionality into scanner and digital camera hardware and software in order to make this metadata readily available for transfer into repositories and digital asset management systems, as well as to make metadata capture more economically viable by reducing the amount of manual entry that is required. This implies a level of trust that the metadata that is automatically captured and internal to the file is inherently correct. See http://www.rlg.org/longterm/autotechmetadata.html for further discussion of this initiative, as well as the discussion on Image Quality Assessment, below. Initiatives such as the Global Digital Format Registry (http://hul.harvard.edu/gdfr/) could potentially help in reducing the number of metadata elements that need to be recorded about a file or group of files regarding file format information necessary for preservation functions. Information maintained in the Registry could be pointed to instead of recorded for each file or batch of files. Structural --Structural metadata describes the relationships between different components of a digital resource. It ties the various parts of a digital resource together in order to make a useable, understandable whole. One of the primary functions of structural metadata is to enable display and navigation, usually via a page-turning application, by indicating the sequence of page images or the presence of multiple views of a multi-part item. In this sense, structural metadata is closely related to the intended behaviors of an object. Structural metadata is very much informed by how the images will be delivered to the user as well as how they will be stored in a repository system in terms of how relationships among objects are expressed. Structural metadata often describes the significant intellectual divisions of an item (such as chapter, issue, illustration, etc.) and correlates these divisions to specific image files. These explicitly labeled access points help to represent the organization of the original object in digital form. This does not imply, however, that the digital must always imitate the organization of the original -- especially for non-linear items, such as folded pamphlets. Structural metadata also associates different representations of the same resource together, such as production master files with their derivatives, or different sizes, views, or formats of the resource. Example structural metadata might include whether the resource is simple or complex (multi-page, multi-volume, has discrete parts, contains multiple views); what the major intellectual divisions of a resource are (table of contents, chapter, musical movement); identification of different views (double-page spread, cover, detail); the extent (in files, pages, or views) of a resource and the proper sequence of files, pages and views; as well as different technical (file formats, size), visual (pre- or post-conservation treatment), intellectual (part of a larger collection or work), and use (all instances of a resource in different formats -- TIFF files for display, PDF files for printing, OCR file for full text searching) versions. -11- File names and organization of files in system directories comprise structural metadata in its barest form. Since meaningful structural metadata can be embedded in file and directory names, consideration of where and how structural metadata is recorded should be done up front. See Section V. Storage for further discussion on this topic. No widely adopted standards for structural metadata exist since most implementations of structural metadata are at the local level and are very dependent on the object being scanned and the desired functionality in using the object. Most structural metadata is implemented in file naming schemes and/or in databases that record the order and hierarchy of the parts of an object so that they can be identified and reassembled back into their original form. The Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard (METS) is often discussed in the context of structural metadata, although it is inclusive of other types of metadata as well. METS provides a way to associate metadata with the digital files they describe and to encode the metadata and the files in a standardized manner, using XML. METS requires structural information about the location and organization of related digital files to be included in the METS document. Relationships between different representations of an object as well as relationships between different hierarchical parts of an object can be expressed. METS brings together a variety of metadata about an object all into one place by allowing the encoding of descriptive, administrative, and structural metadata. Metadata and content information can either be wrapped together within the METS document, or pointed to from the METS document if they exist in externally disparate systems. METS also supports extension schemas for descriptive and administrative metadata to accommodate a wide range of metadata implementations. Beyond associating metadata with digital files, METS can be used as a data transfer syntax so objects can easily be shared; as a Submission Information Package, an Archival Information Package, and a Dissemination Information Package in an OAIS-compliant repository (see below); and also as a driver for applications, such as a page turner, by associating certain behaviors with digital files so that they can be viewed, navigated, and used. Because METS is primarily concerned with structure, it works best with "library-like" objects in establishing relationships among multi-page or multi-part objects, but it does not apply as well to hierarchical relationships that exist in collections within an archival context. See http://www.loc.gov/standards/mets/ for more information on METS. Behavior --Behavior metadata is often referred to in the context of a METS object. It associates executable behaviors with content information that define how a resource should be utilized or presented. Specific behaviors might be associated with different genres of materials (books, photographs, Powerpoint presentations) as well as with different file formats. Behavior metadata contains a component that abstractly defines a set of behaviors associated with a resource as well as a "mechanism" component that points to executable code (software applications) that then performs a service according to the defined behavior. The ability to associate behaviors or services with digital resources is one of the attributes of a METS object and is also part of the "digital object architecture" of the Fedora digital repository system. See http://www.fedora.info/documents/master-spec-12.20.02.pdf for a discussion of Fedora and digital object behaviors. Preservation --Preservation metadata encompasses all information necessary to manage and preserve digital assets over time. Preservation metadata is usually defined in the context of the OAIS reference model (Open Archival Information System, http://ssdoo.gsfc.nasa.gov/nost/isoas/overview.html), and is often linked to the functions and activities of a repository. It differs from technical metadata in that it documents processes performed over time (events or actions taken to preserve data and the outcomes of these events) as opposed to explicitly describing provenance (how a digital resource was created) or file format characteristics, but it does encompass all types of the metadata mentioned above, including rights information. Although preservation metadata draws on information recorded earlier (technical and structural metadata would be necessary to render and reassemble the resource into an understandable whole), it is most often associated with analysis of and actions performed on a resource after submission to a repository. Preservation metadata might include a record of changes to the resource, such as transformations or conversions from format to format, or indicate the nature of relationships among different resources. Preservation metadata is information that will assist in preservation decision-making regarding the long-term value of a digital resource and the cost of maintaining access to it, and will help to both facilitate archiving strategies for digital images as well as support and document these strategies over time. Preservation metadata is commonly linked with digital preservation strategies such as migration and emulation, as well as more "routine" system-level actions such as copying, backup, or other automated processes carried out on large numbers of objects. These strategies will rely on all types of pre-existing metadata and will also generate and record new -12- metadata about the object. It is likely that this metadata will be both machine-processable and "human-readable" at different levels to support repository functions as well as preservation policy decisions related to these objects.In its close link to repository functionality, preservation metadata may reflect or even embody the policy decisions of a repository; but these are not necessarily the same policies that apply to preservation and reformatting in a traditional context. The extent of metadata recorded about a resource will likely have an impact on future preservation options to maintain it. Current implementations of preservation metadata are repository- or institution-specific. We anticipate that a digital asset management system may provide some basic starter functionality for low-level preservation metadata implementation, but not to the level of a repository modeled on the OAIS. See also A Metadata Framework to Support the Preservation of Digital Objects at http://www.oclc.org/research/projects/pmwg/pm_framework.pdf and Preservation Metadata for Digital Objects: A Review of the State of the Art at http://www.oclc.org/research/projects/pmwg/presmeta_wp.pdf, both by the OCLC/RLG Working Group on Preservation Metadata, for excellent discussions of preservation metadata in the context of the OAIS model. A new working group, "Preservation Metadata: Implementation Strategies," is working on developing best practices for implementing preservation metadata and on the development of a recommended core set of preservation metadata. Their work can be followed at http://www.oclc.org/research/projects/pmwg/. For some examples of implementations of preservation metadata element sets at specific institutions, see: OCLC Digital Archive Metadata, at http://www.oclc.org/support/documentation/pdf/da_metadata_elements.pdf; Florida Center for Library Automation Preservation Metadata, at http://www.fcla.edu/digitalArchive/pdfs/Archive_data_dictionary20030703.pdf; Technical Metadata for the Long-Term Management of Digital Materials, at http://dvl.dtic.mil/metadata_guidelines/TechMetadata_26Mar02_1400.pdf; and The National Library of New Zealand, Metadata Standard Framework, Preservation Metadata, at http://www.natlib.govt.nz/files/4initiatives_metaschema_revised.pdf. Image quality assessment (NARA-NWTS Digital Imaging Lab proposed metadata requirement)-The technical metadata specified in the NISO Data Dictionary -- Technical Metadata for Digital Still Images contains many metadata fields necessary for the long-term viability of the image file. However, we are not convinced that it goes far enough in providing information necessary to make informed preservation decisions regarding the value and quality of a digital still raster image. Judgments about the quality of an image require a visual inspection of the image, a process that cannot be automated. Quality is influenced by many factors -- such as the source material from which the image was scanned, the devices used to create the image, any subsequent processing done to the image, compression, and the overall intended use of the image. Although the data dictionary includes information regarding the analog source material and the scanning environment in which the image was created, we are uncertain whether this information is detailed enough to be of use to administrators, curators, and others who will need to make decisions regarding the value and potential use of digital still images. The value of metadata correlates directly with the future use of the metadata. It seems that most technical metadata specified in the NISO data dictionary is meant to be automatically captured from imaging devices and software and intended to be used by systems to render and process the file, not necessarily used by humans to make decisions regarding the value of the file. The metadata can make no guarantee about the quality of the data. Even if files appear to have a full complement of metadata and meet the recommended technical specifications as outlined in these Technical Guidelines, there may still be problems with the image file that cannot be assessed without some kind of visual inspection. The notion of an image quality assessment was partly inspired by the National Library of Medicine Permanence Ratings (see http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/reports/permanence.pdf and http://www.rlg.org/events/pres-2000/byrnes.html), a rating for resource permanence or whether the content of a resource is anticipated to change over time. However, we focused instead on evaluating image quality and this led to the development of a simplified rating system that would: indicate a quality level for the suitability of the image as a production master file (its suitability for multiple uses or outputs), and serve as a potential metric that could be used in making preservation decisions about whether an image is worth maintaining over time. If multiple digital versions of a single record exist, then the image quality assessment rating may be helpful for deciding which version(s) to keep. The rating is linked to image defects introduced in the creation of intermediates and/or introduced during digitization and image processing, and to the nature and severity of the defects based on evaluating the digital -13- images on-screen at different magnifications. In essence, a "good" rating for image files implies an appropriate level of image quality that warrants the effort to maintain them over time.The image quality assessment takes into account the attributes that influence specifications for scanning a production master image file: format, size, intended use, significant characteristics of the original that should be maintained in the scan, and the quality and characteristics of the source material being scanned. This rating system could later be expanded to take into account other qualities such as object completeness (are all pages or only parts of the resource scanned?); the source of the scan (created in-house or externally provided?); temporal inconsistencies (scanned at different times, scanned on different scanners, scan of object is pre- or post-conservation treatment?), and enhancements applied to the image for specific purposes (for exhibits, cosmetic changes among others). This rating is not meant to be a full technical assessment of the image, but rather an easy way to provide information that supplements existing metadata about the format, intent, and use of the image, all of which could help determine preservation services that could be guaranteed and associated risks based on the properties of the image. We anticipate a preservation assessment will to be carried out later in the object's lifecycle based on many factors, including the image quality assessment. Image quality rating metadata is meant to be captured at the time of scanning, during processing, and even at the time of ingest into a repository. When bringing batches or groups of multiple image files into a repository that do not have individual image quality assessment ratings, we recommend visually evaluating a random sample of images and applying the corresponding rating to all files in appropriate groups of files (such as all images produced on the same model scanner or all images for a specific project). Record whether the image quality assessment rating was applied as an individual rating or as a batch rating. If a batch rating, then record how the files were grouped. -14-

As stated earlier, image quality assessment rating is applied to the digital image but is also linked to information regarding the source material from which it was scanned. Metadata about the image files includes a placeholder for information regarding source material, which includes a description of whether the analog source is the original or an intermediate, and if so, what kind of intermediate (copy, dupe, microfilm, photocopy, etc.) as well as the source format. Knowledge of deficiencies in the source material (beyond identifying the record type and format) helps to inform image quality assessment as well. The practicality of implementing this kind of assessment has not yet been tested, especially since it necessitates a review of images at the file level. Until this conceptual approach gains broader acceptance and consistent implementation within the community, quality assessment metadata may only be useful for local preservation decisions. As the assessment is inherently technical in nature, a basic foundation in photography and imaging is -15- helpful in order to accurately evaluate technical aspects of the file, as well as to provide a degree of trustworthiness in the reviewer and in the rating that is applied.Records management/recordkeeping --Another type of metadata, relevant to the digitization of federal records in particular, is records management metadata. Records management metadata is aligned with administrative-type metadata in that its function is to assist in the management of records over time; this information typically includes descriptive (and, more recently, preservation) metadata as a subset of the information necessary to both find and manage records. Records management metadata is usually discussed in the context of the systems or domains in which it is created and maintained, such as Records Management Application (RMA) systems. This includes metadata about the records as well as the organizations, activities, and systems that create them. The most influential standard in the United States on records management metadata is the Department of Defense's Design Criteria Standard for Electronic Records Management Software Applications (DOD 5015.2) at http://www.dtic.mil/whs/directives/corres/html/50152std.htm. This standard focuses on minimum metadata elements a RMA should capture and maintain, defines a set of metadata elements at the file plan, folder, and record levels, and generally discusses the functionality that an RMA should have as well as the management, tracking, and integration of metadata that is held in RMAs. Records Management metadata should document whether digital images are designated as permanent records, new records, temporary records, reference copies, or are accorded a status such as "indefinite retention." A determination of the status of digital images in a records management context should be made front at the point of creation of the image, as this may have an effect on the level and detail of metadata that will be gathered for a digital object to maintain its significant properties and functionality over the long term. Official designation of the status of the digital images will be an important piece of metadata to have as digital assets are brought into a managed system, such as NARA's Electronic Records Archive (ERA), which will have extensive records management capabilities. In addition to a permanent or temporary designation, records management metadata should also include documentation on any access and/or usage restrictions for the image files. Metadata documenting restrictions that apply to the images could become essential if both unrestricted and restricted materials and their metadata are stored and managed together in the same system, as these files will possess different maintenance, use and access requirements. Even if restricted files are stored on a physically separate system for security purposes, metadata about these files may not be segregated and should therefore include information on restrictions. For digitization projects done under NARA 816 guidance, we assume classified, privacy restricted, and any records with other restrictions will not be selected for digitization. However, records management metadata should still include documentation on access and usage restrictions -- even unrestricted records should be identified as "unrestricted." This may be important metadata to express at the system level as well, as controls over access to and use of digital resources might be built directly into a delivery or access system. In the future, documentation on access and use restrictions relevant to NARA holdings might include information such as: "classified" (which should be qualified by level of classification); "unclassified" or "unrestricted;" "declassified;" and "restricted," (which should be qualified by a description of the restrictions, i.e., specific donor-imposed restrictions), for example. Classification designation will have an impact on factors such as physical storage (files may be physically or virtually stored separately), who has access to these resources, and different maintenance strategies. Basic records management metadata about the image files will facilitate bringing them into a formal system and will inform functions such as scheduling retention timeframes, how the files are managed within a system, what types or levels of preservation services can be performed, or how they are distributed and used by researchers, for example. Tracking --Tracking metadata is used to control or facilitate the particular workflow of an imaging project during different stages of production. Elements might reflect the status of digital images as they go through different stages of the workflow (batch information and automation processes, capture, processing parameters, quality control, archiving, identification of where/media on which files are stored); this is primarily internally-defined metadata that serves as documentation of the project and may also serve also serve as a statistical source of information to track and report on progress of image files. Tracking metadata may exist in a database or via a directory/folder system. -16- Meta-metadata --Although this information is difficult to codify, it usually refers to metadata that describes the metadata record itself, rather than the object it is describing, or to high-level information about metadata "policy" and procedures, most often on the project level. Meta-metadata documents information such as who records the metadata, when and how it gets recorded, where it is located, what standards are followed, and who is responsible for modification of metadata and under what circumstances. It is important to note that metadata files yield "master" records as well. These non-image assets are subject to the same rigor of quality control and storage as master image files. Provisions should be made for the appropriate storage and management of the metadata files over the long term. Assessment of Metadata Needs for Imaging Projects:Before beginning any scanning, it is important to conduct an assessment both of existing metadata and metadata that will be needed in order to develop data sets that fit the needs of the project. The following questions frame some of the issues to consider:

-17- Local Implementation:Because most of what we scan comes to the Imaging Lab on an item-by-item basis, we are capturing minimal descriptive and technical metadata at the item level only during the image capture and processing stage. Until a structure into which we can record hierarchical information both about the objects being scanned and their higher-level collection information is in place, we are entering basic metadata in files using Adobe Photoshop. Information about the file is added to the IPTC (International Press Telecommunications Council) fields in Photoshop in anticipation of mapping these values to an external database. The IPTC fields are used as placeholder fields only. This information is embedded in the file using Adobe XMP (Extensible Metadata Platform: http://www.adobe.com/products/xmp/main.html). Primary identifier is automatically imported into the "File -19- Info" function in Photoshop from our scanning software. We anticipate implementing the Custom Panel Description File Format feature available in XMP to define our own metadata set and then exporting this data into an asset management system, since the data will be stored in easily migratable XML packets.The following tables outline minimal descriptive, technical, and structural metadata that we are currently capturing at the

file level (table indicates the elements that logically apply at the object level):

* Describes physical attributes of the source material that may assist in interpretation of image quality; describes capture and processing decisions; or indicates known problems with the original media that may affect the quality of the scan. A controlled vocabulary is used for these fields. We feel that it is important to record source object information in technical metadata. Knowledge of the source material will inform image quality assessment and future preservation decisions. For images derived from another digital image, source information will be described in a relationship field, most likely from a set of typed relationships (e.g., "derived from"). -20- Technical metadata is currently entered into an external project database to describe specific derivative files. We anticipate that this information will map up to attributes of the production master files. The following table describes suggested minimum technical metadata fields for production masters.

* See "Image Quality Assessment" discussion above. Structural metadata is currently embedded into the file name in a sequential numbering scheme for multi-part items and is reflected in working file directory structures. We anticipate that the file name, which follows the scheme: unique ID_scan year_component part_image role.format extension, can be parsed so that component parts of a digital resource can be logically related together. We also record minimal structural metadata in the header information, such as "front" and "back" for double-sided items or "cover," "page 1," "page 2," "double-page spread" etc. for multi-page items or multi-views. "Component part" is strictly a file sequence number and does not reflect actual page numbers. This metadata is currently recorded as text since the data is not intended to feed into any kind of display or navigation application at the moment. Relationships --Currently there is no utility to record basic relationships among multi-page or multi-part image files beyond documenting relationships in file names. Until a digital asset management system is in place, our practice is to capture as much metadata as possible in the surrounding file structure (names, directories, headers). However, we consider that simple labels or names for file identifiers coupled with more sophisticated metadata describing relationships across files are the preferred way forward to link files together. This metadata would include file identifiers and metadata record identifiers and a codified or typed set of relationships that would help define the associations between image files and between different representations of the same resource. (Relationships between the digital object and the analog source object or the place of the digital object in a larger collection hierarchy would be documented elsewhere in descriptive metadata). Possible relationship types include identification of principal or authoritative version (for production master file); derivation relationships indicating what files come from what files; whether the images were created in the lab or come from another source; structural relationships (for multi-page or -part objects); sibling relationships (images of the same intellectual resource, but perhaps scanned from different source formats). We intend to further refine our work on relationships in the coming months, and start to define metadata that is specific to aggregations of files. Batch level metadata --Currently, data common to all files produced in the Imaging Lab (such as byte order, file format, etc.) is not recorded at the logical level at this time, but we anticipate integrating this kind of information into the construction of a digital asset management system. We are continuing discussions on how to formalize "Lab common -21- knowledge," such as details about the hardware and software configurations used to scan and process digital images, target information, and capture and image processing methodologies into our technical metadata specifications.Permanent and temporary metadata --When planning for a digital imaging project, it may not be necessary to save all metadata created and used during the digitization phase of the project. For example, some tracking data may not be needed once all quality control and redo work has been completed. It may not be desirable, or necessary, to bring all metadata into a digital repository. For NARA's pilot Electronic Access Project, metadata fields that were calculated from other fields, such as square area of a document (used during the pre-scan planning phase to determine scanning resolution and size of access file derivatives), were not saved in the final database since they could be recalculated in the future. Also, it may not be desirable or necessary to provide access to all metadata that is maintained within a system to all users. Most administrative and technical metadata will need to be accessible to administrative users to facilitate managing the digital assets, but does not need to be made available to general users searching the digital collections. III. TECHNICAL OVERVIEWRaster Image Characteristics:Spatial Resolution --Spatial resolution determines the amount of information in a raster image file in terms of the number of picture elements or pixels per unit measurement, but it does not define or guarantee the quality of the information. Spatial resolution defines how finely or widely spaced the individual pixels are from each other. The higher the spatial resolution the more finely spaced and the larger number of pixels overall. The lower the spatial resolution the more widely spaced the pixels and the fewer number of pixels overall. Spatial resolution is measured as pixels per inch or PPI, also pixels per millimeter or pixels per centimeter are used. Resolution is often referred to as dots per inch or DPI, in common usage the terms PPI and DPI are used interchangeably. Since raster image files are composed of pixels, technically PPI is a more accurate term and is used in this document (one example in support of using the PPI term is that Adobe Photoshop software uses the pixels per inch terminology). DPI is the appropriate term for describing printer resolution (actual dots vs. pixels); however, DPI is used often in scanning and image processing software to refer to spatial resolution and this usage is an understandable convention. The spatial resolution and the image dimensions determine the total number of pixels in the image; an 8"x10" photograph scanned at 100 ppi produces an image that has 800 pixels by 1000 pixels or a total of 800,000 pixels. The numbers of rows and columns of pixels, or the height and width of the image in pixels as described in the previous sentence, is known as the pixel array. When specifying a desired file size, it is always necessary to provide both the resolution and the image dimensions; ex. 300 ppi at 8"x10" or even 300 ppi at original size. The image file size, in terms of data storage, is proportional to the spatial resolution (the higher the resolution, the larger the file size for a set document size) and to the size of the document being scanned (the larger the document, the larger the file size for a set spatial resolution). Increasing resolution increases the total number of pixels resulting in a larger image file. Scanning larger documents produces more pixels resulting in larger image files. Higher spatial resolution provides more pixels, and generally will render more fine detail of the original in the digital image, but not always. The actual rendition of fine detail is more dependent on the spatial frequency response of the scanner or digital camera (see Quantifying Scanner/Digital Camera Performance below), the image processing applied, and the characteristics of the item being scanned. Also, depending on the intended usage of the production master files, there may be a practical limit to how much fine detail is actually needed. Signal Resolution --Bit-depth or signal resolution, sometimes called tonal resolution, defines the maximum number of shades and/or colors in a digital image file, but does not define or guarantee the quality of the information. In a 1-bit file each pixel is represented by a single binary digit (either a 0 or 1), so the pixel can be either black or white. There are only two possible combinations or 21 = 2. -22- The common standard for grayscale and color images is to use 8-bits (eight binary digits representing each pixel) of data per channel and this provides a maximum of 256 shades per channel ranging from black to white; 28 = 256 possible combinations of zeroes and ones. High-bit or 16-bits (16 binary digits representing each pixel) per channel images can have a greater number of shades compared to 8-bit per channel images, a maximum of over 65,000 shades vs. 256 shades; 216 -- 65,536 possible combinations of zeroes and ones. Well done 8-bits per channel imaging will meet most needs; with a limited ability for major corrections, transformations, and re-purposing because gross corrections of 8-bit per channel images may cause shades to drop out of the image, creating a posterization effect, due to the limited number of shades. High-bit images can match the effective shading and density range of photographic originals (assuming the scanner is actually able to capture the information), and, due to the greater shading (compared to 8-bits per channel), may be beneficial when re-purposing images and when working with images that need major or excessive adjustments to the tone distribution and/or color balance. However, at this time, monitors for viewing images and output devices for printing images all render high-bit images at 8-bits per pixel, so there is limited practical benefit to saving high-bit images and no way to verify the accuracy and quality of high-bit images. Also, it is best to do a good job during digitization to ensure accurate tone and color reproduction, rather than relying on post-scan correction of high-bit images. Poorly done high-bit imaging has no benefit. Color Mode --Grayscale image files consist of a single channel, commonly either 8-bits (256 levels) or 16-bits (65,536 levels) per pixel with the tonal values ranging from black to white. Color images consist of three or more grayscale channels that represent color and brightness information, common color modes include RGB (red, green, blue), CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow, black), and LAB (lightness, red-green, blue-yellow). The channels in color files may be either 8 bits (256 levels) or 16-bits (65,536 levels). Display and output devices mathematically combine the numeric values from the multiple channels to form full color pixels, ranging from black to white and to full colors. RGB represents an additive color process -- red, green and blue light are combined to form white light. This is the approach commonly used by computer monitors and televisions, film recorders that image onto photographic film, and digital printers/enlargers that print to photographic paper. RGB files have three color channels: 3 channels x 8 bits = 24-bit color file or 3 channels x 16-bits = 48-bit color. All scanners and digital cameras create RGB files, by sampling for each pixel the amount of light passing through red, green and blue filters that is reflected or transmitted by the item or scene being digitized. Black is represented by combined RGB levels of 0-0-0, and white is represented by combined RGB levels of 255-255-255. This is based on 8-bit imaging and 256 levels from 0 to 255; this convention is used for 16-bit imaging as well, despite the greater number of shades. All neutral colors have equal levels in all three color channels. A pure red color is represented by levels of 255-0-0, pure green by 0-255-0, and pure blue by 0-0-255. CMYK files are an electronic representation of a subtractive process -- cyan (C), magenta (M) and yellow (Y) are combined to form black. CMYK mode files are used for prepress work and include a fourth channel representing black ink (K). The subtractive color approach is used in printing presses (four color printing), color inkjet and laser printers (four color inks, many photo inkjet printers now have more colors), and almost all traditional color photographic processes (red, green and blue sensitive layers that form cyan, magenta and yellow dyes). LAB color mode is a device independent color space that is matched to human perception -- three channels representing lightness (L, equivalent to a grayscale version of the image), red and green information (A), and blue and yellow information (B). LAB mode benefits would include the matching to human perception and they do not require color profiles (see section on color management), disadvantages include the potential loss of information in the conversion from the RGB mode files from scanners and digital cameras, need to have high-bit data, and few applications and file formats support the mode. Avoid saving files in CMYK mode, CMYK files have a significantly reduced color gamut (see section on color management) and are not suitable for production master image files for digital imaging projects involving holdings/collections in cultural institutions. While theoretically LAB may have benefits, at this time we feel that RGB files produced to the color and tone reproduction described in these guidelines and saved with an Adobe RGB 1998 color profile are the most practical option for production master files and are relatively device independent. We acknowledge our workflow to produce RGB production master files may incur some level of loss of data, however we believe the benefits of using RGB files brought to a common rendering outweigh the minor loss. -23- Digitization Environment:Our recommendations and the ISO standards referred to below are based on using CRT monitors. Most LCD monitors we have tested do not compare in quality to the better CRTs in rendering fine detail and smooth gradients. Also, LCD monitors may have artifacts that make it difficult to distinguish image quality problems in the image files, and the appearance of colors and monitor brightness shift with the viewing angle of the LCD panel. This is changing rapidly and the image quality of current high-end LCD monitors is very close to the quality of better CRT monitors. If used, LCD monitors should meet the criteria specified below. Viewing conditions --A variety of factors will affect the appearance of images, whether displayed or printed on reflective, transmissive or emissive devices or media. Those factors that can be quantified must be controlled to assure proper representation of an image. We recommend following the guidance in the following standards --

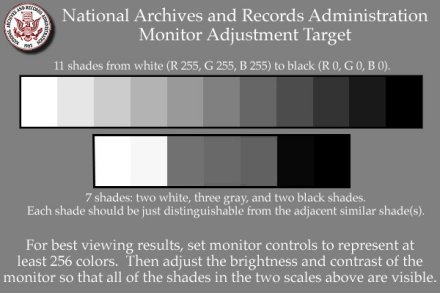

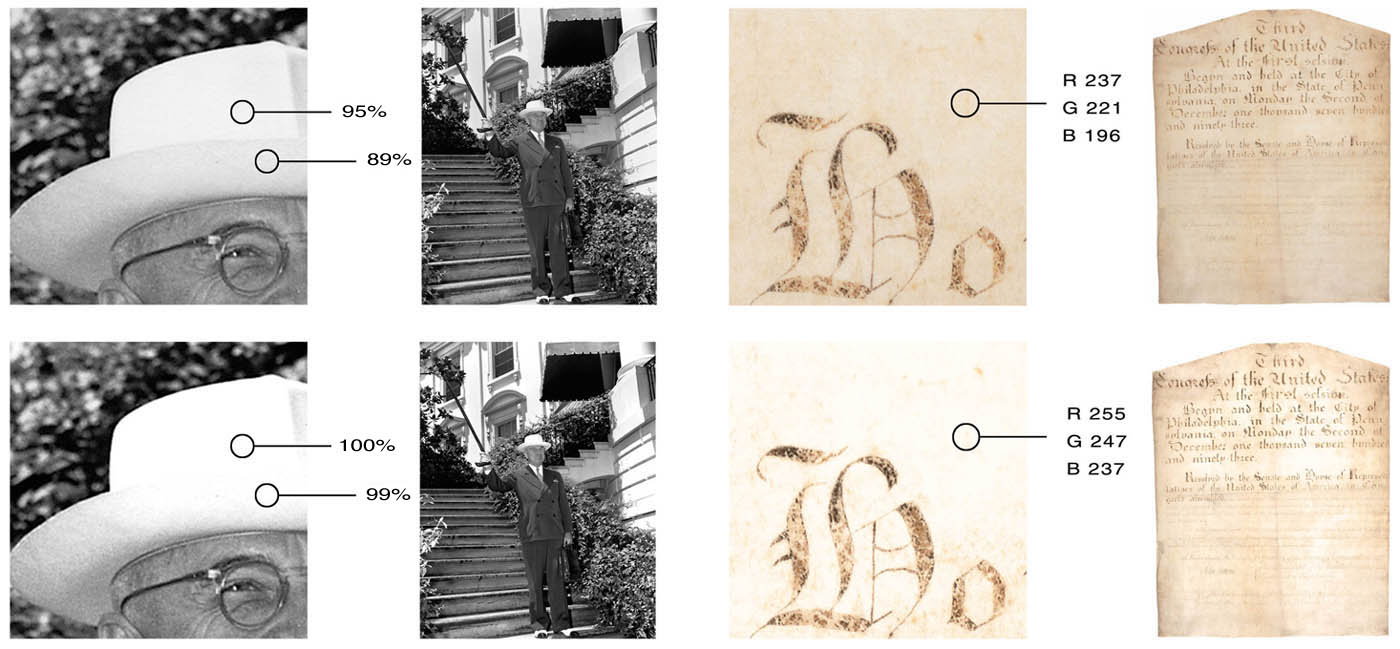

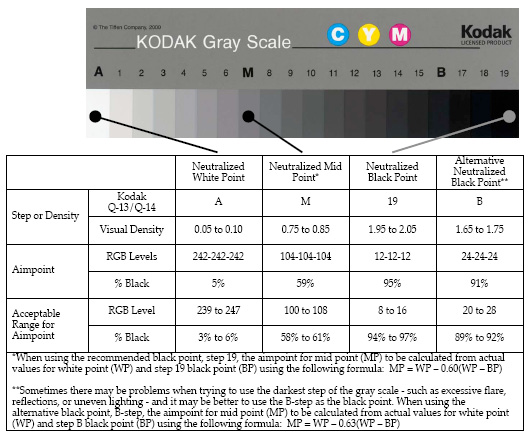

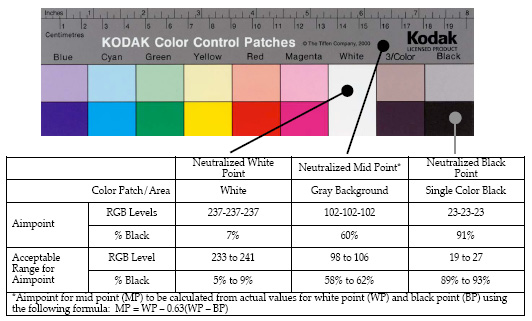

NOTE -- The following are common parameters controlled by users, however refer to the standards for complete requirements and test methods. In particular, ISO 12646 specifies additional hardware requirements for monitors to ensure a reasonable quality level necessary for comparison to hardcopy. Monitor settings, light boxes, and viewing booths --We assume the assessment of many digital images will be made in comparison to the originals that have been digitized, therefore ISO 12646 should be followed where it supplements or differs from ISO 3664. We recommend digital images be viewed on a computer monitor set to 24 bits (millions of colors) or greater, and calibrated to a gamma of 2.2. ISO 12646 recommends the color temperature of the monitor also be set to 5000K (D50 illuminant) to match the white point of the illumination used for viewing the originals. Monitor luminance level must be at least 85 cd/m2, and should be 120 cd/m2 or higher. The computer/monitor desktop should be set to a neutral gray background (avoid images, patterns, and/or strong colors), preferably no more than 10% of the maximum luminance of the screen. For viewing originals, we recommend using color correct light boxes or viewing booths that have a color temperature of 5000K (D50 illuminant), as specified in ISO 3664. ISO 3664 provides two luminance levels for viewing originals, ISO 12646 recommends using the lower levels (P2 and T2) when comparing to the image on screen. The actual illumination level on originals should be adjusted so the perceived brightness of white in the originals matches the brightness of white on the monitor. The room --The viewing environment should be painted/decorated a neutral, matte gray with a 60% reflectance or less to minimize flare and perceptual biases. Monitors should be positioned to avoid reflections and direct illumination on the screen. -24- ISO 12646 requires the room illumination be less than 32 lux when measured anywhere between the monitor and the observer, and the light a color temperature of approximately 5000K. Practical experience --In practice, we have found a tolerable range of deviation from the measurements required in the ISO standards. When the ambient room lighting is kept below the limit set in ISO 12646, its color temperature can be lower than 5000K, as long as it is less than the monitor color temperature. To compensate for environments that may not meet the ISO standards, as well as difficulties comparing analog originals to images on a monitor, the color temperature may need to be set higher than 5000K so that the range of grays from white to black appears neutral when viewed in the actual working environment. The higher color temperature may also be necessary for older monitors to reach an appropriate brightness, as long as neutrals don't appear too blue when compared to neutral hardcopy under the specified illumination. Monitor calibration --In order to meet and maintain the monitor settings summarized above, we recommend using CRT monitors designed for the graphic arts, photography, or multimedia markets. A photosensor-based color calibrator and appropriate software (either bundled with the monitor or a third party application) should be used to calibrate the monitor to the aims discussed above. This is to ensure desired color temperature, luminance level, neutral color balance, and linearity of the red, green, and blue representation on the monitor are achieved. If using an ICC color managed workflow (see section on color management), an ICC profile should be created after monitor calibration for correct rendering of images. The monitor should be checked regularly and recalibrated when necessary. Using a photo sensor-based monitor calibrator, however, does not always ensure monitors are calibrated well. Ten years of practical experience has shown calibrators and calibration software may not work accurately or consistently. After calibration, it is important to assess the monitor visually, to make sure the monitor is adjusted appropriately. Assess overall contrast, brightness, and color neutrality of the gray desktop. Also, evaluate both color neutrality and detail rendering in white and black areas. This can be done using an image target of neutral patches ranging from black to white and saved in LAB color mode (since LAB does not require an ICC profile and can be viewed independently of the color managed process). In addition, it may be helpful to evaluate sample images or scans of targets -- such as the NARA Monitor Adjustment Target (shown below) and/or a known image such as a scan of a Kodak grayscale adjusted to the aimpoints (8-8-8/105-105-105/247-247-247) described below.

Quantifying Scanner/Digital Camera Performance:Much effort has gone into quantifying the performance of scanners and digital cameras in an objective manner. The following tests are used to check the capabilities of digitization equipment, and provide information on how to best use the equipment. -25- Even when digitization equipment is assessed as described below, it is still necessary to have knowledgeable and experienced staff to evaluate images visually. At this time, it is not possible to rely entirely on the objective test measurements to ensure optimum image quality. It is still necessary to have staff with the visual literacy and technical expertise to do a good job with digitization and to perform quality control for digital images. This is true for the digitization of all types of archival records, but very critical for the digitization of photographic images. Also, these tests are useful when evaluating and comparing scanners and digital cameras prior to purchase. Ask manufacturers and vendors for actual test results, rather than relying on the specifications provided in product literature, some performance claims in product literature are often overstated. If test results are not available, then try to scan test targets during a demonstration and consider having the analyses performed by a contract service. During digitization projects, tests should be performed on a routine basis to ensure scanners and digital cameras/copy systems are performing optimally. Again, if it is not possible to analyze the tests in-house, then consider having a service perform the analyses on the resulting image files. The following standards either are available or are in development, these test methods can be used for objective assessment of scanner or digital camera/copy system performance --

These standards can be purchased from ISO at http://www.iso.ch or from IHS Global at http://global.ihs.com. At this time, test methods and standards do not exist for all testing and device combinations. However, many tests are applicable across the range of capture device types and are cited in the existing standards as normative references. Other test methods may be used to quantify scanner/digital camera performance. We anticipate there will be additional standards and improved test methods developed by the group working on the above standards. Unfortunately, at this time image analysis software is expensive and complex making it difficult to perform all the tests needed to properly quantify scanner/digital camera performance. Also, there is a range of test targets needed for these tests and they can be expensive to purchase. The following requirements for performance criteria are based on measurements of the variety of actual scanners and digital cameras used in the NWTS Digital Imaging Lab. Where limits are specified, the limits are based on the performance of equipment we consider subjectively acceptable. This subjective acceptability is based on many years combined staff experience in the fields of photography, of photographic reformatting and duplication of a variety of archival records, and of digital imaging and digitization of a variety of archival records. No digitization equipment or system is perfect, they all have trade-offs in regards to image quality, speed, and cost. The engineering of scanners and digital cameras represents a compromise, and for many markets image quality is sacrificed for higher speed and lower cost of equipment. Many document and book scanners, office scanners (particularly inexpensive ones), and high-speed scanners (all types) may not meet the limits specified, particularly for properties like image noise. Also, many office and document scanners are set at the default to force the paper of the original document to pure white in the image, clipping all the texture and detail in the paper (not desirable for most originals in collections of cultural institutions). These scanners will not be able to meet the desired tone reproduction without recalibration (which may not be possible), without changing the scanner settings (which may not overcome the problem), or without modification of the scanner and/or software (not easily done). Test Frequency and Equipment Variability:After equipment installation and familiarization with the hardware and software, an initial performance capability evaluation should be conducted to establish a baseline for each specific digitization device. At a minimum, this benchmark assessment would include for example --

-26- Many scanners can be used both with the software/device drivers provided by the manufacturer and with third-party software/device drivers, characterize the device using the specific software/device drivers to be used for production digitization. Also, performance can change dramatically (and not always for the better) when software/device drivers are updated, characterize the device after every update. A full suite of tests should be conducted to quantify the performance of digitization systems. Some tests probably only need to be redone on an infrequent basis, while others will need to be done on a routine basis. Depending on the performance consistency of equipment, consider performing tests using production settings on a weekly basis or for each batch of originals, whichever comes first. You may want to perform appropriate tests at the beginning of each batch and at the end of each batch to confirm digitization was consistent for the entire batch. Scanner/digital camera performance will vary based on actual operational settings. Tests can be used to optimize scanner/camera settings. The performance of individual scanners and digital cameras will vary over time (see test frequency above). Also, the performance of different units of the same model scanner/camera will vary. Test every individual scanner/camera with the specific software/device driver combination(s) used for production. Perform appropriate test(s) any time there is an indication of a problem. Compare these results to past performance through a cumulative database. If large variability is noted from one session to the next for given scanner/camera settings, attempt to rule out operator error first. Tests:Opto-electronic conversion function (OECF) -- for grayscale and color imaging --

Dynamic range -- for grayscale and color imaging --

Spatial frequency response (SFR) -- for grayscale and color imaging --

Noise -- for grayscale and color imaging --

Channel registration -- for color imaging --

Uniformity -- illumination, color, lens coverage, etc. -- for gray scale and color imaging --

Dimensional accuracy - for 1-bit, grayscale, and color imaging --

Other artifacts or imaging problems --